[Chronological snobbery is] the uncritical acceptance of the intellectual climate common to our own age and the assumption that whatever has gone out of date is on that account discredited. (C. S. Lewis, Surprised by Joy, p. 207.)

I was guilty of chronological snobbery in High School. My snobbery was not intentional, but practical, an indifference, apathy, and laziness toward history and Latin – those classes were too much work! I can blame the snobbery on my immaturity, and my immaturity on my youth, but it was aided and encouraged by a Zeitgeist that valued “modernity” and “progress” over tradition and classical education. For example, my high school implemented a new open approach to English classes that allowed me to bypass traditional literature courses for film and media studies (this was in the mid-1970s). Only when I was older did I realize how foolish my attitude and choices were.

I might still be guilty of chronological snobbery, but I now concede that there are some old ways of doing things which are still valid, and in many ways superior to newer ways of doing things. For example, Bach, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Brahms all either studied or were influenced by Johann Joseph Fux’s Gradus ad Parnassum, a book with influence that spanned at least two centuries and three major musical stylistic periods. Its influence can still be seen in modern counterpoint texts and courses.

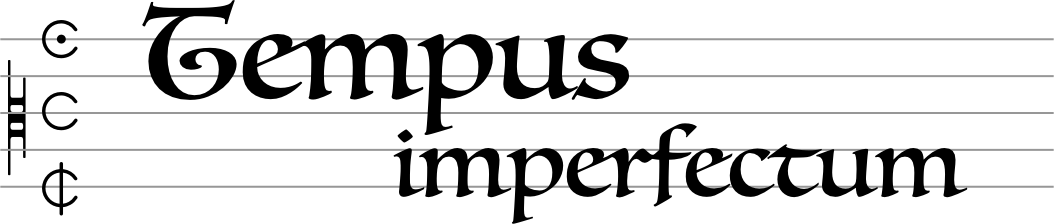

Actually, species counterpoint (Fux’s contrapuntal method) is still a thing. Counterpoint and other rule-based, abstract approaches to studying music theory and composition, such as four-part voice-leading exercises, encourage and develop mental and procedural habits that provide a strong basis for evaluating and refining creative musical processes. Unfortunately, modern music technology and a focus on immediate gratification have made it possible to detour around these seemingly mundane and outdated procedures, and with them the mental discipline that results from pursuing them.

Certainly this . . .

Fun & Exciting (Beatmaker 3)!!

. . . is more appealing than this . . .

Boring (Open Music Theory)?

(From Open Music Theory: Composing a First-Species Counterpoint (Kris Shaffer)

In the long run, musicians who work at the latter (counterpoint and similar exercises) are likely to be in a better position to create appealing and enduring music than those who ignore it. This is not to say that studying strict counterpoint is a prerequisite to making appealing music, but the habits of mind that composers of the past cultivated through their study and practice of things like counterpoint produced a “mental infrastructure” that allowed them to create music that, by virtue of its adherence to principles that transcend temporal styles, has endured. Contemporary musicians (or would-be musicians) make a mistake if they assume that there is nothing to learn from the past. I’m often struck by how “stuck” popular music can be in its own idioms (this, for example). The best musicians draw from a well that is both wide and deep.

On the other hand, exclusive reliance on printed music can also be a form of “chronological snobbery.” Popular music is often (but not always) created in an aural, improvisatory, and technological context, with less (if any) reliance on notated sheet music. Interestingly, classical musicians and teachers are starting to realize the value of these skills (see here and here for examples). After all, Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven were all gifted improvisers, and C. P. E. Bach devoted an entire section of his Versuch über die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen (Essay on the true Art of playing Keyboard Instruments) to the art of improvisation and realizing figured bass. The classical emphasis on interpreting and being faithful to the composer’s score has resulted in training and practice that often ignores or minimizes the development of improvisational skills.

Yo-Yo Ma, the famous cellist, is among a small but growing group of very famous classical musicians who are leading the way in a new way of making music that incorporates a blend of improvisation, classical sensibility, and popular or folk music traditions. There are also a number of popular and jazz musicians doing the same thing – musicians like Wynton and Branford Marsalis, Sting, The Bad Plus, Bobby McFerrin, Pat Metheny, Brad Mehldau, and Bela Fleck.

Concerning the first type of “chronological snobbery” (among non-classical musicians), there are good reasons for studying music and musical techniques of the past. Even though musical styles vary and change, there are certain underlying principles that don’t change, and which can be applied to a wide range of styles. The Austrian music theorist Heinrich Schenker recognized this. As Steve Larson points out,

Schenker emphasized – as the essential pedagogical meaning of species counterpoint – a focus on “fundamental musical problems”:

The purpose of counterpoint, rather than to teach a specific style of composition, is to lead the ear of the serious student of music for the first time into the infinite world of fundamental musical problems. Constantly, at every opportunity, the student’s ear must be alerted to the psychological effects . . .

One appeal here is that “the infinite world of fundamental musical problems” is relevant to pieces as varied as a Bach prelude, a Beethoven sonata, and a Brahms song (in fact, I would argue that this “world of fundamental musical problems” is also relevant to repertoire much broader than that which interested Schenker). Note also the emphasis on “the ear” – Schenker returns repeatedly to this point. (Steve Larson, “Another Look at Schenker’s Counterpoint,” Indiana Theory Review Vol. 15, No. 1 (Spring 1994), pp. 36-37)

This viewpoint is echoed and expanded by the editors of the Open Music Theory textbook:

The “fundamental musical problems” we will address in the study of counterpoint center around the way in which some basic principles of auditory perception and cognition (how the brain perceives and conceptualizes sound) play out in Western musical structure. (Open Music Theory, “Introduction to strict voice-leading”)

Concerning the second type of “chronological snobbery” (among classical musicians), there are also good reasons for incorporating aural and improvisatory skills in music-making. In any case, creating music in a satisfactory manner requires much work, practice, and study. Amateur musicians and dilettantes might prefer to take a narrow, limited approach which keeps them happy in their world, but those who are responsible for producing music for a larger audience can continually work to broaden and strengthen their experience, knowledge, and skills if they want to produce music of lasting value.

Links:

Yo-Yo Ma, Bobby McFerrin, Edgar Meyer, Mark O’Connor – Hush Little Baby

Wynton Marsalis on Classical Music

Bela Fleck – Bach Partita No. 1003 / Sinister Minister

The Bad Plus – Variation d’Apollon (Stravinsky)

Behind Pat Metheny’s “Road to the Sun”, written for LAGQ